After exposure and adhesion, the next step in pathogenesis is invasion, which can involve enzymes and toxins. Many pathogens achieve invasion by entering the bloodstream, an effective means of dissemination because blood vessels pass close to every cell in the body. The downside of this mechanism of dispersal is that the blood also includes numerous elements of the immune system. Various terms ending in –emia are used to describe the presence of pathogens in the bloodstream. The presence of bacteria in blood is called bacteremia. Bacteremia involving pyogens (pus-forming bacteria) is called pyemia. When viruses are found in the blood, it is called viremia. The term toxemia describes the condition when toxins are found in the blood. If bacteria are both present and multiplying in the blood, this condition is called septicemia.

Patients with septicemia are described as septic, which can lead to shock, a life-threatening decrease in blood pressure (systolic pressure <90 mm Hg) that prevents cells and organs from receiving enough oxygen and nutrients. Some bacteria can cause shock through the release of toxins (virulence factors that can cause tissue damage) and lead to low blood pressure. Gram-negative bacteria are engulfed by immune system phagocytes, which then release tumor necrosis factor, a molecule involved in inflammation and fever. Tumor necrosis factor binds to blood capillaries to increase their permeability, allowing fluids to pass out of blood vessels and into tissues, causing swelling, or edema (Figure 15.10). With high concentrations of tumor necrosis factor, the inflammatory reaction is severe and enough fluid is lost from the circulatory system that blood pressure decreases to dangerously low levels. This can have dire consequences because the heart, lungs, and kidneys rely on normal blood pressure for proper function; thus, multi- organ failure, shock, and death can occur.

Exoenzymes

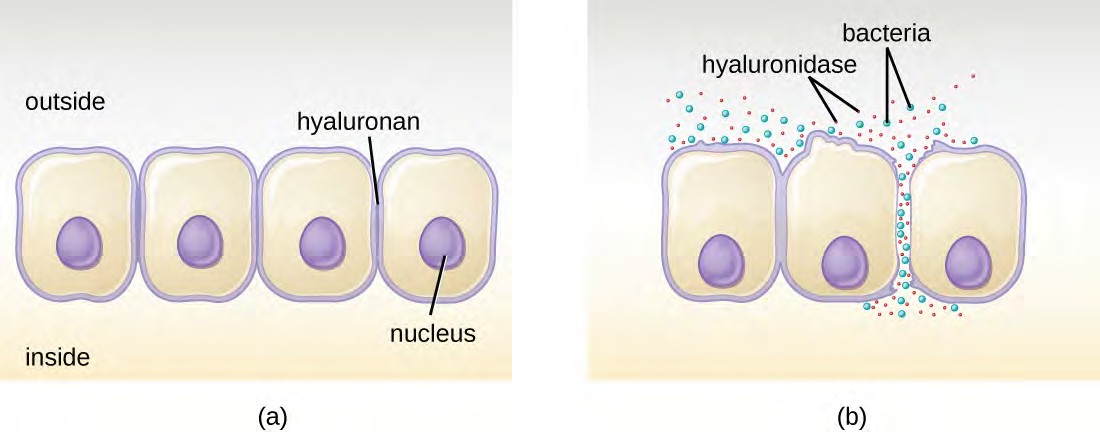

Some pathogens produce extracellular enzymes, or exoenzymes, that enable them to invade host cells and deeper tissues. Exoenzymes have a wide variety of targets. Some general classes of exoenzymes and associated pathogens are listed in Table 15.8. Each of these exoenzymes functions in the context of a particular tissue structure to facilitate invasion or support its own growth and defend against the immune system. For example, hyaluronidase S, an enzyme produced by pathogens like Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Clostridium perfringens, degrades the glycoside hylauronan (hyaluronic acid), which acts as an intercellular cement between adjacent cells in connective tissue (Figure 15.11). This allows the pathogen to pass through the tissue layers at the portal of entry and disseminate elsewhere in the body (Figure 15.11).

Some Classes of Exoenzymes and Their Targets

|

Glycohydrolases

|

Hyaluronidase S in Staphylococcus aureus | Degrades hyaluronic acid that cements cells together to promote spreading through tissues

|

|

Nucleases

|

DNAse produced by S. aureus | Degrades DNA released by dying cells (bacteria and host cells) that can trap the bacteria, thus promoting spread

|

|

Phospholipases

|

Phospholipase C of Bacillus anthracis | Degrades phospholipid bilayer of host cells, causing cellular lysis, and degrade membrane of phagosomes to enable escape into the cytoplasm

|

|

Proteases

|

Collagenase in Clostridium perfringens | Degrades collagen in connective tissue to promote spread

|

Table 15.8

Figure 15.11 (a) Hyaluronan is a polymer found in the layers of epidermis that connect adjacent cells. (b) Hyaluronidase produced by bacteria degrades this adhesive polymer in the extracellular matrix, allowing passage between cells that would otherwise be blocked.

Pathogen-produced nucleases, such as DNAse produced by S. aureus, degrade extracellular DNA as a means of escape and spreading through tissue. As bacterial and host cells die at the site of infection, they lyse and release their intracellular contents. The DNA chromosome is the largest of the intracellular molecules, and masses of extracellular DNA can trap bacteria and prevent their spread. S. aureus produces a DNAse to degrade the mesh of extracellular DNA so it can escape and spread to adjacent tissues. This strategy is also used by S. aureus and other pathogens to degrade and escape webs of extracellular DNA produced by immune system phagocytes to trap the bacteria.

Enzymes that degrade the phospholipids of cell membranes are called phospholipases. Their actions are specific in regard to the type of phospholipids they act upon and where they enzymatically cleave the molecules. The pathogen responsible for anthrax, B. anthracis, produces phospholipase C. When B. anthracis is ingested by phagocytic cells of the immune system, phospholipase C degrades the membrane of the phagosome before it can fuse with the lysosome, allowing the pathogen to escape into the cytoplasm and multiply. Phospholipases can also target the membrane that encloses the phagosome within phagocytic cells. As described earlier in this chapter, this is the mechanism used by intracellular pathogens such as L. monocytogenes and Rickettsia to escape the phagosome and multiply within the cytoplasm of phagocytic cells. The role of phospholipases in bacterial virulence is not restricted to phagosomal escape. Many pathogens produce phospholipases that act to degrade cell membranes and cause lysis of target cells. These phospholipases are involved in lysis of red blood cells, white blood cells, and tissue cells.

Bacterial pathogens also produce various protein-digesting enzymes, or proteases. Proteases can be classified according to their substrate target (e.g., serine proteases target proteins with the amino acid serine) or if they contain metals in their active site (e.g., zinc metalloproteases contain a zinc ion, which is necessary for enzymatic activity).

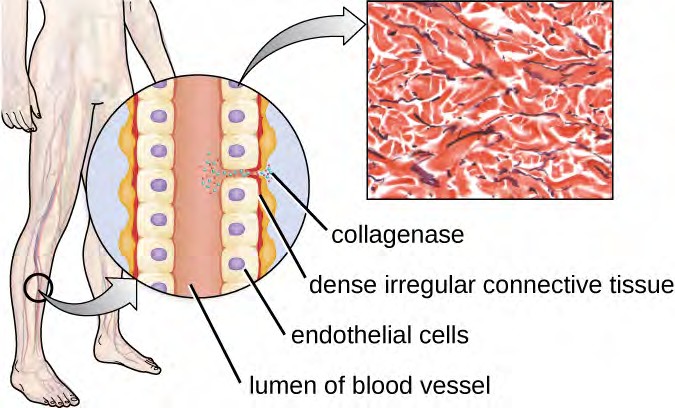

One example of a protease that contains a metal ion is the exoenzyme collagenase. Collagenase digests collagen, the dominant protein in connective tissue. Collagen can be found in the extracellular matrix, especially near mucosal membranes, blood vessels, nerves, and in the layers of the skin. Similar to hyaluronidase, collagenase allows the pathogen to penetrate and spread through the host tissue by digesting this connective tissue protein. The collagenase produced by the gram-positive bacterium Clostridium perfringens, for example, allows the bacterium to make its way through the tissue layers and subsequently enter and multiply in the blood (septicemia). C. perfringens then uses toxins and a phospholipase to cause cellular lysis and necrosis. Once the host cells have died, the bacterium produces gas by fermenting the muscle carbohydrates. The widespread necrosis of tissue and accompanying gas are characteristic of the condition known as gas gangrene (Figure 15.12).

Figure 15.12 The illustration depicts a blood vessel with a single layer of endothelial cells surrounding the lumen and dense connective tissue (shown in red) surrounding the endothelial cell layer. Collagenase produced by C. perfringens degrades the collagen between the endothelial cells, allowing the bacteria to enter the bloodstream. (credit illustration: modification of work by Bruce Blaus; credit micrograph: Micrograph provided by the Regents of University of Michigan Medical School © 2012)

Toxins

In addition to exoenzymes, certain pathogens are able to produce toxins, biological poisons that assist in their ability to invade and cause damage to tissues. The ability of a pathogen to produce toxins to cause damage to host cells is called toxigenicity.

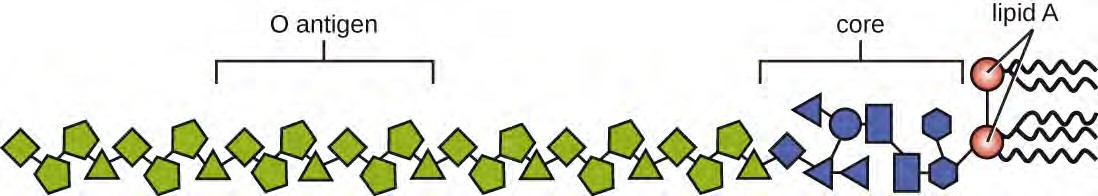

Toxins can be categorized as endotoxins or exotoxins. The lipopolysaccharide (LPS) found on the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria is called endotoxin (Figure 15.13). During infection and disease, gram-negative bacterial pathogens release endotoxin either when the cell dies, resulting in the disintegration of the membrane, or when the bacterium undergoes binary fission. The lipid component of endotoxin, lipid A, is responsible for the toxic properties of the LPS molecule. Lipid A is relatively conserved across different genera of gram-negative bacteria; therefore, the toxic properties of lipid A are similar regardless of the gram-negative pathogen. In a manner similar to that of tumor necrosis factor, lipid A triggers the immune system’s inflammatory response (see Inflammation and Fever). If the concentration of endotoxin in the body is low, the inflammatory response may provide the host an effective defense against infection; on the other hand, high concentrations of endotoxin in the blood can cause an excessive inflammatory response, leading to a severe drop in blood pressure, multi-organ failure, and death.

Figure 15.13 Lipopolysaccharide is composed of lipid A, a core glycolipid, and an O-specific polysaccharide side chain. Lipid A is the toxic component that promotes inflammation and fever.

A classic method of detecting endotoxin is by using the Limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL) test. In this procedure, the blood cells (amebocytes) of the horseshoe crab (Limulus polyphemus) is mixed with a patient’s serum. The amebocytes will react to the presence of any endotoxin. This reaction can be observed either chromogenically (color) or by looking for coagulation (clotting reaction) to occur within the serum. An alternative method that has been used is an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) that uses antibodies to detect the presence of endotoxin.

Unlike the toxic lipid A of endotoxin, exotoxins are protein molecules that are produced by a wide variety of living pathogenic bacteria. Although some gram-negative pathogens produce exotoxins, the majority are produced by gram- positive pathogens. Exotoxins differ from endotoxin in several other key characteristics, summarized in Table 15.9. In contrast to endotoxin, which stimulates a general systemic inflammatory response when released, exotoxins are much more specific in their action and the cells they interact with. Each exotoxin targets specific receptors on specific cells and damages those cells through unique molecular mechanisms. Endotoxin remains stable at high temperatures, and requires heating at 121 °C (250 °F) for 45 minutes to inactivate. By contrast, most exotoxins are heat labile because of their protein structure, and many are denatured (inactivated) at temperatures above 41 °C (106 °F). As discussed earlier, endotoxin can stimulate a lethal inflammatory response at very high concentrations and has a measured LD50 of 0.24 mg/kg. By contrast, very small concentrations of exotoxins can be lethal. For example, botulinum toxin, which causes botulism, has an LD50 of 0.000001 mg/kg (240,000 times more lethal than endotoxin).

Comparison of Endotoxin and Exotoxins Produced by Bacteria

|

Source

|

Gram-negative bacteria

| Gram-positive (primarily) and gram-negative bacteria

|

|

Composition

|

Lipid A component of lipopolysaccharide

| Protein

|

|

Effect on host

|

General systemic symptoms of inflammation and fever

| Specific damage to cells dependent upon receptor-mediated targeting of cells and specific mechanisms of action

|

|

Heat stability

|

Heat stable

| Most are heat labile, but some are heat stable

|

|

LD50 |

High

| Low

|

Table 15.9

The exotoxins can be grouped into three categories based on their target: intracellular targeting, membrane disrupting, and superantigens. Table 15.10 provides examples of well-characterized toxins within each of these three categories.

Some Common Exotoxins and Associated Bacterial Pathogens

|

Intracellular- targeting toxins

|

Cholera toxin

| Vibrio cholerae | Activation of adenylate cyclase in intestinal cells, causing increased levels of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and secretion of fluids and electrolytes out of cell, causing diarrhea

|

|

Tetanus toxin

| Clostridium tetani | Inhibits the release of inhibitory neurotransmitters in the central nervous system, causing spastic paralysis

|

|

Botulinum toxin

| Clostridium botulinum | Inhibits release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine from neurons, resulting in flaccid paralysis

|

|

Diphtheria toxin

| Corynebacterium diphtheriae | Inhibition of protein synthesis, causing cellular death

|

|

Membrane- disrupting toxins

|

Streptolysin

| Streptococcus pyogenes | Proteins that assemble into pores in cell membranes, disrupting their function and killing the cell

|

|

Pneumolysin

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | |

|

Alpha-toxin

| Staphylococcus aureus | |

|

Alpha-toxin

| Clostridium perfringens | Phospholipases that degrade cell membrane phospholipids, disrupting membrane function and killing the cell

|

|

Phospholipase C

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | |

|

Beta-toxin

| Staphylococcus aureus | |

|

Superantigens

|

Toxic shock syndrome toxin

| Staphylococcus aureus | Stimulates excessive activation of immune system cells and release of cytokines (chemical mediators) from immune system cells. Life-threatening fever, inflammation, and shock are the result.

|

|

Streptococcal mitogenic exotoxin

| Streptococcus pyogenes | |

|

Streptococcal pyrogenic toxins

| Streptococcus pyogenes | |

Table 15.10

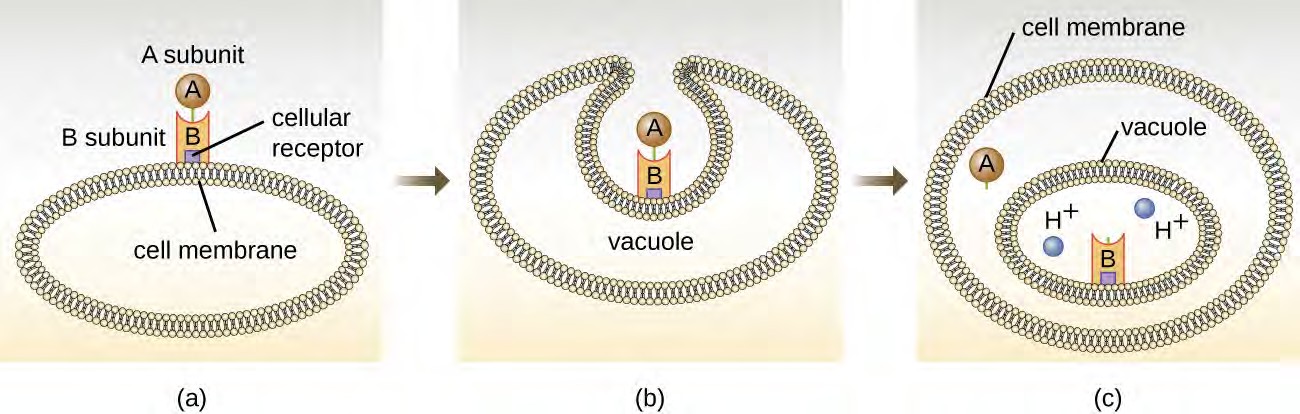

The intracellular targeting toxins comprise two components: A for activity and B for binding. Thus, these types of toxins are known as A-B exotoxins (Figure 15.14). The B component is responsible for the cellular specificity of the toxin and mediates the initial attachment of the toxin to specific cell surface receptors. Once the A-B toxin binds to the host cell, it is brought into the cell by endocytosis and entrapped in a vacuole. The A and B subunits separate as the vacuole acidifies. The A subunit then enters the cell cytoplasm and interferes with the specific internal cellular function that it targets.

Figure 15.14 (a) In A-B toxins, the B component binds to the host cell through its interaction with specific cell surface receptors. (b) The toxin is brought in through endocytosis. (c) Once inside the vacuole, the A component (active component) separates from the B component and the A component gains access to the cytoplasm. (credit: modification of work by “Biology Discussion Forum”/YouTube)

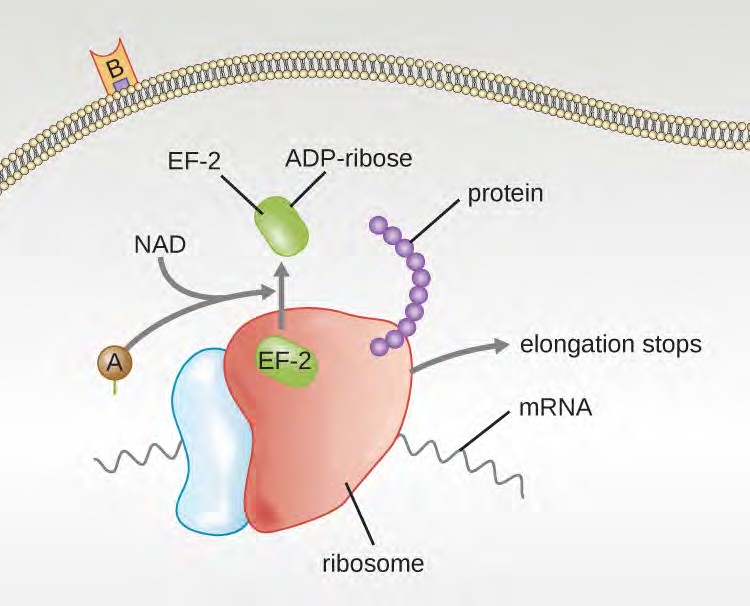

Four unique examples of A-B toxins are the diphtheria, cholera, botulinum, and tetanus toxins. The diphtheria toxin is produced by the gram-positive bacterium Corynebacterium diphtheriae, the causative agent of nasopharyngeal and cutaneous diphtheria. After the A subunit of the diphtheria toxin separates and gains access to the cytoplasm, it facilitates the transfer of adenosine diphosphate (ADP)-ribose onto an elongation-factor protein (EF-2) that is needed for protein synthesis. Hence, diphtheria toxin inhibits protein synthesis in the host cell, ultimately killing the cell (Figure 15.15).

Figure 15.15 The mechanism of the diphtheria toxin inhibiting protein synthesis. The A subunit inactivates elongation factor 2 by transferring an ADP-ribose. This stops protein elongation, inhibiting protein synthesis and killing the cell.

Cholera toxin is an enterotoxin produced by the gram-negative bacterium Vibrio cholerae and is composed of one A subunit and five B subunits. The mechanism of action of the cholera toxin is complex. The B subunits bind to receptors on the intestinal epithelial cell of the small intestine. After gaining entry into the cytoplasm of the epithelial cell, the A subunit activates an intracellular G protein. The activated G protein, in turn, leads to the activation of the enzyme adenyl cyclase, which begins to produce an increase in the concentration of cyclic AMP (a secondary messenger molecule). The increased cAMP disrupts the normal physiology of the intestinal epithelial cells and causes

them to secrete excessive amounts of fluid and electrolytes into the lumen of the intestinal tract, resulting in severe “rice-water stool” diarrhea characteristic of cholera.

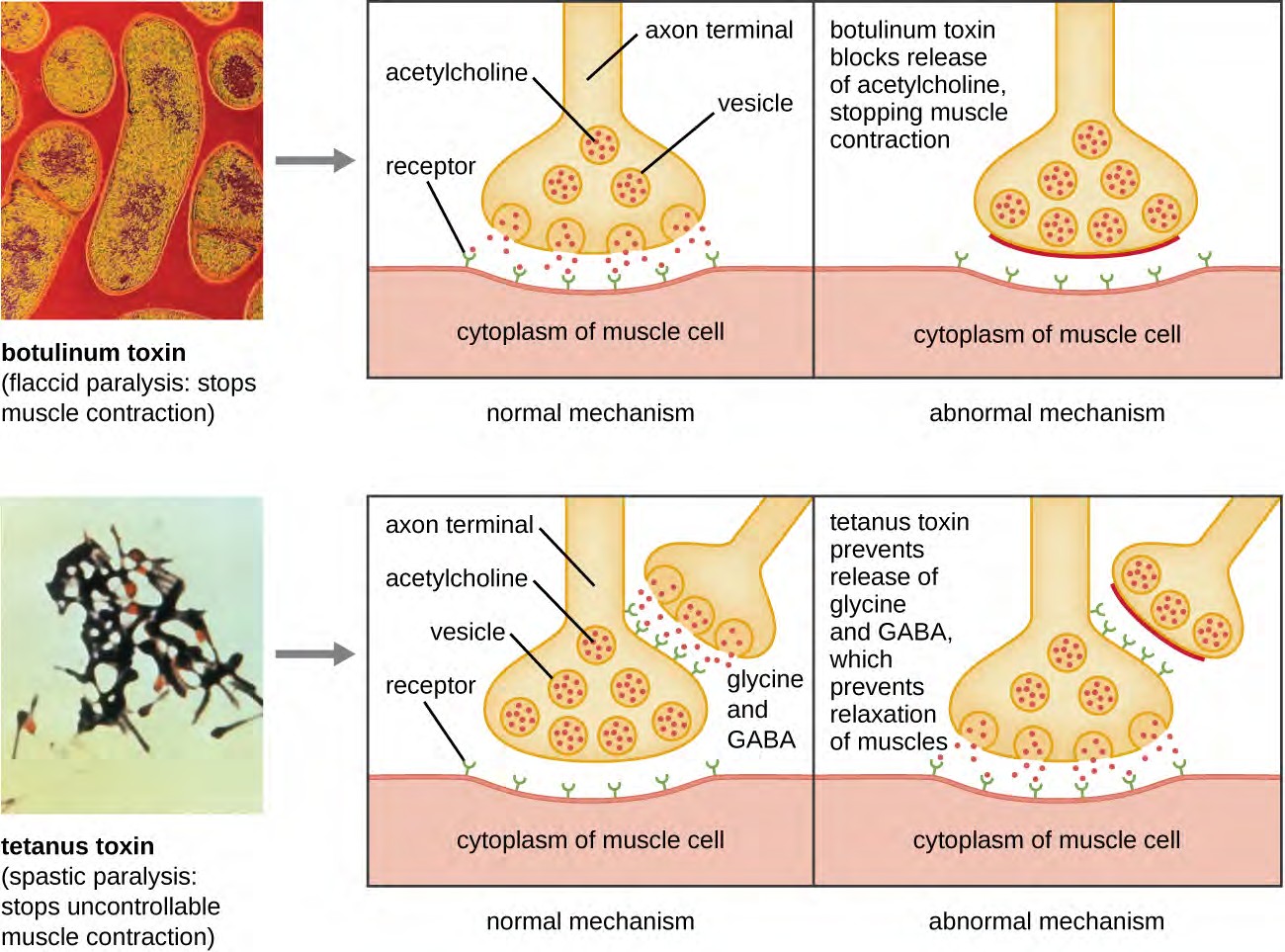

Botulinum toxin (also known as botox) is a neurotoxin produced by the gram-positive bacterium Clostridium botulinum. It is the most acutely toxic substance known to date. The toxin is composed of a light A subunit and heavy protein chain B subunit. The B subunit binds to neurons to allow botulinum toxin to enter the neurons at the neuromuscular junction. The A subunit acts as a protease, cleaving proteins involved in the neuron’s release of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter molecule. Normally, neurons release acetylcholine to induce muscle fiber contractions. The toxin’s ability to block acetylcholine release results in the inhibition of muscle contractions, leading to muscle relaxation. This has the potential to stop breathing and cause death. Because of its action, low concentrations of botox are used for cosmetic and medical procedures, including the removal of wrinkles and treatment of overactive bladder.

Another neurotoxin is tetanus toxin, which is produced by the gram-positive bacterium Clostridium tetani. This toxin also has a light A subunit and heavy protein chain B subunit. Unlike botulinum toxin, tetanus toxin binds to inhibitory interneurons, which are responsible for release of the inhibitory neurotransmitters glycine and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). Normally, these neurotransmitters bind to neurons at the neuromuscular junction, resulting in the inhibition of acetylcholine release. Tetanus toxin inhibits the release of glycine and GABA from the interneuron, resulting in permanent muscle contraction. The first symptom is typically stiffness of the jaw (lockjaw). Violent muscle spasms in other parts of the body follow, typically culminating with respiratory failure and death. Figure

shows the actions of both botulinum and tetanus toxins.

Figure 15.16 Mechanisms of botulinum and tetanus toxins. (credit micrographs: modification of work by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

Membrane-disrupting toxins affect cell membrane function either by forming pores or by disrupting the phospholipid bilayer in host cell membranes. Two types of membrane-disrupting exotoxins are hemolysins and leukocidins, which form pores in cell membranes, causing leakage of the cytoplasmic contents and cell lysis. These toxins were originally thought to target red blood cells (erythrocytes) and white blood cells (leukocytes), respectively, but we now know they can affect other cells as well. The gram-positive bacterium Streptococcus pyogenes produces streptolysins, water- soluble hemolysins that bind to the cholesterol moieties in the host cell membrane to form a pore. The two types of streptolysins, O and S, are categorized by their ability to cause hemolysis in erythrocytes in the absence or presence of oxygen. Streptolysin O is not active in the presence of oxygen, whereas streptolysin S is active in the presence of oxygen. Other important pore-forming membrane-disrupting toxins include alpha toxin of Staphylococcus aureus and pneumolysin of Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Bacterial phospholipases are membrane-disrupting toxins that degrade the phospholipid bilayer of cell membranes rather than forming pores. We have already discussed the phospholipases associated with B. anthracis, L. pneumophila, and Rickettsia species that enable these bacteria to effect the lysis of phagosomes. These same phospholipases are also hemolysins. Other phospholipases that function as hemolysins include the alpha toxin of Clostridium perfringens, phospholipase C of P. aeruginosa, and beta toxin of Staphylococcus aureus.

Some strains of S. aureus also produce a leukocidin called Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL). PVL consists of two subunits, S and F. The S component acts like the B subunit of an A-B exotoxin in that it binds to glycolipids on the outer plasma membrane of animal cells. The F-component acts like the A subunit of an A-B exotoxin and carries the enzymatic activity. The toxin inserts and assembles into a pore in the membrane. Genes that encode PVL are more frequently present in S. aureus strains that cause skin infections and pneumonia.[8] PVL promotes skin infections by

causing edema, erythema (reddening of the skin due to blood vessel dilation), and skin necrosis. PVL has also been shown to cause necrotizing pneumonia. PVL promotes pro-inflammatory and cytotoxic effects on alveolar leukocytes. This results in the release of enzymes from the leukocytes, which, in turn, cause damage to lung tissue.

The third class of exotoxins is the superantigens. These are exotoxins that trigger an excessive, nonspecific stimulation of immune cells to secrete cytokines (chemical messengers). The excessive production of cytokines, often called a cytokine storm, elicits a strong immune and inflammatory response that can cause life-threatening high fevers, low blood pressure, multi-organ failure, shock, and death. The prototype superantigen is the toxic shock syndrome toxin of S. aureus. Most toxic shock syndrome cases are associated with vaginal colonization by toxin- producing S. aureus in menstruating women; however, colonization of other body sites can also occur. Some strains of Streptococcus pyogenes also produce superantigens; they are referred to as the streptococcal mitogenic exotoxins and the streptococcal pyrogenic toxins.

Describe how exoenzymes contribute to bacterial invasion.

Explain the difference between exotoxins and endotoxin.

Name the three classes of exotoxins.